For some time now, we have been covering all the ways in which thiamine deficiency influences disease. The primary mechanisms are through the down regulation of mitochondrial enzymes critical for ATP production. The lack of thiamine impairs mitochondrial functioning significantly leading to complex, debilitating, chronic, and sometimes, deadly illnesses. With mitochondrial energy a requisite for cell functioning and survival it is easy to see how the diminishment of mitochondrial functioning would negatively impact health and how high-energy physiological systems like the nervous and cardiovascular systems might be particularly hard hit. More than just just derailing cell function, as if that wasn’t problematic enough, when mitochondrial energy production slows, the adaptive cascades that ensue include epigenetic modification, not only at the level of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), but also, at the level of gene expression from the cell nucleus or nDNA. This is a huge discovery with broad implications about health and disease. It means that all sorts of things considered innocuous, are directly influencing gene activation and deactivation by way of the mitochondria.

Epigenetics: How the Cells Adapt to the Environment

Epigenetic modification refers to the activation or deactivation of chromosomal gene expression absent mutation. These changes can be heritable and often are. Strictly speaking, epigenetics involves changes in methylation, histone modification and/or alterations in non-coding RNA that affect transcription. Epigenetics is the way our genome adapts to environmental circumstances and prepares our offspring to do the same. The majority of epigenetic work focuses on genomic changes. That is, those variables that affect gene expression from the cell nucleus or nDNA. There is a growing body of evidence, however, that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are affected by epigenetic factors in much the same way as nDNA. In fact, given the mitochondria’s role in cell survival, one might suspect that mitochondria are more susceptible to environmental epigenetics, perhaps even the first responders and/or the initiators of chromosomal genetic changes.

Considering that nDNA accounts for over 90% of the proteins involved in mitochondrial functioning, how could damaged mitochondria, even functionally inefficient mitochondria, not affect gene expression in the cell’s nucleus? Though we tend to think of mitochondria as self-contained and discrete entities, black boxes of sorts, where stuff goes in and ATP magically comes out, this is not only not the case, it seems biologically illogical to think that way. So much of mitochondrial functioning is related to its environmental milieu. In fact, increasingly researchers are finding that the mitochondria are the center of the organismal universe, sensing and signaling danger, and effectively, regulating all adaptive responses, including epigenetic modification of the proteins encoded by the cell nucleus.

Beyond the strict definition of epigenetics, it seems to me that any factor that altered mitochondrial function, would eventually alter gene expression by any number of mechanisms, not just the direct ones. That is, because the mitochondria produce the energy required for cell survival, anything that derails their capacity to produce ATP, pharmaceutical and environmental chemicals, for example, should be considered, ipso facto, epigenetic modulators. Energy is a fundamental requirement for life. How could energy depletion not affect gene expression? It does, and now we know how.

Starve the Mitochondria, Alter the Genome

It turns out, when the mitochondria are starving and/or damaged the key enzyme complex that sits atop the entire energy production pathway and is critical for the production of the substrates involved directly (yes, I said directly) with gene expression, migrates from the mitochondria across the cell and into the cell’s nucleus where it then sets up shop and begins its work there. Sit with that for a minute. The entire enzyme complex decides that things are not working where it is, so it hitches a ride with some transporter proteins, several of them along the way, to find a more suitable home. The enzyme complex ‘knows’ that its functions are critical for survival and so it must move or die. What an incredible bit of adaptive capacity. A symbiosis, if you will.

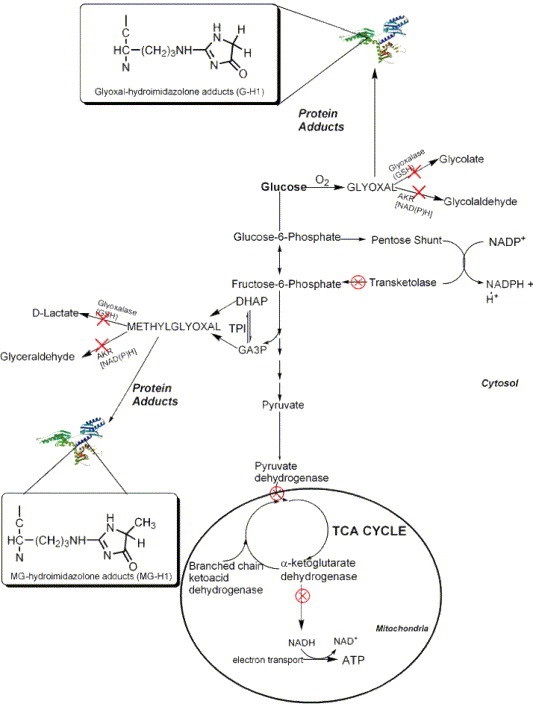

To make matters even more interesting, the traveling enzyme complex just so happens to be the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and you guessed it, the PDC is highly, and I mean highly, thiamine dependent. But wait, there’s more. Several other enzymes involved in mitochondrial bioenergetics are also thiamine dependent. These include: alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α- KGDH) in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) or citric acid cycle, transketolase (TKT) within the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), the branched chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (BCKDC) involved in amino acid catabolism and, more recently, thiamine has be identified as a co-factor in fatty acid metabolism via an enzyme called 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase (HACL1) in the peroxisomes (organelles that break down fatty acids before transporting them to the mitochondria). So thiamine deficiency is problematic. It not only causes dysfunction in the mitochondria, reducing bioenergetic capacity, but if severe enough and/or chronic, it alters the genome. And those changes are likely heritable. That is, your thiamine deficiency likely will affect your children’s ability to process thiamine.

Thiamine Deficiency and Gene Expression

Without sufficient thiamine, the PDC enzyme complex does not function well and because of its geographic position at the entry point into the citric acid cycle, when it is not working at capacity, everything below it eventually grinds to a halt resulting in severe neurological and neuromuscular deficits. Absent congenital PDC disorders, however, when it simply is inefficient or starved for its cofactors, metabolic disorders ensue because we cannot convert carbohydrates into ATP and the sugars that normally would be converted into energy, remain unmetabolized, floating around outside the cells and causing the whole cascade of effects that mark type 2 diabetes. When the PDC is inefficient, ATP levels wane and fatigue ensues. Systems that are highly energy dependent are hit the hardest. Think brain, heart, muscles, GI tract. When mitochondria are inefficient or damaged, reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase. Anti-oxidant capacity decreases and further damage to the PDC ensues. Inflammation increases, immune function decreases. Cell level hypoxia grows. Alternative energy pathways are activated, those that are endemic of cancer. Yes, cancer can be considered a metabolic disorder.

When the PDC is inefficient, mtDNA heteroplasmy, the balance between mutated mtDNA and healthy mtDNA grows with each mitogenic cycle. This, of course, further derails mitochondrial capacity (and increases the need for thiamine). Absent available resources, mitochondrial death cascades are initiated. And now, we know at some point in this disease and death spiral, when ATP diminishes and the litany of adaptive measures fail to maintain sufficient energy availability, the PDC up and leaves its mitochondrion and sets up shop in the cell nucleus, in what is presumably a last ditch effort to save its cell and the organism as a whole. What a remarkable bit of adaptive capacity.

The researchers, who discovered this, ruled out the possibility that the PDC enzyme complex was already in the cell nucleus. It wasn’t. It traveled by way of several transporter proteins. They also found that once in the nucleus, it began producing acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA). Acetyl-CoA is requisite for the acetylation and deacetylation of histones, post translational changes in DNA, but also lysine acetylation, which further affects metabolism – mitochondrial energy homeostasis. With insufficient acetyl-CoA and insufficient acetylation, DNA replication is aberrant. Moreover, without sufficient acetyl-CoA, acetylcholine synthesis, an incredibly important transmitter for nervous system functioning, diminishes.

A Constitutively Active Enzyme: What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Even more interesting, the PDC in the cell nucleus appears to be constitutively active. Unlike in healthy mitochondria where checks and balances prevail, when the PDC travels to the nucleus it has no feedback control to temper its activity. The enzymes that normally shut down PDC production (pyruvate dehyrodgenase kinase) in the mitochondria, were not present in the cell nucleus, and thus, once the PDC was turned on, it stayed on. That means when the PDC translocates to the cell nucleus it operates independently much like a Warburg effect in cancer metabolism; one that fully supplants healthier metabolic pathways. Can you say tumorogenesis?

This research has enormous implications for everything from cancer to Alzheimer’s disease and everything in between that involves metabolic disturbances like diabetes and heart disease. Metabolism begins and ends with the mitochondria, at the PDC, and the PDC is highly dependent on thiamine. Every pharmaceutical and environmental chemical damages the mitochondria in some manner or another and that damage inevitably reduces ATP capacity. Some chemicals also deplete thiamine directly, thus downregulating the activity of the PDC and the other thiamine dependent enzymes. Even when these chemicals don’t deplete thiamine directly, the western diet is more often than not thiamine deficient, sometimes only marginally, others time quite significantly so with symptoms already expressed, but very rarely recognized. We have known that thiamine was critical for health and survival for some time. Now we have one more reason to tread carefully with lifestyles and exposures that deplete thiamine.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

David Goodsell, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This article was first published on April 25, 2017.