Ondine is a mythological figure whose tale goes back to the ancient Greeks. She is described as a water nymph who fell in love with a mortal male. He is said to have eventually jilted her, causing her to curse him. She abolished automatic controls in his body so that he had to remember them and control them consciously. This included automatic breathing. Eventually he became so tired that he fell asleep. Automatic breathing ceased and he died. The Ondine character has appeared and reappeared throughout history and must have represented a phenomenon that had been observed many times as a cause of an inexplicable sudden death at night.

Automatic Breathing, Apnea, SIDs, and Ondine’s Curse

The human brain is connected to the spinal cord by means of a part of the brain called the brainstem. It contains nerve centers that deal with the control of automatic breathing. These centers are connected, through the autonomic nervous system, to the muscles and organs that control breathing, explaining why breathing continues without our having to think about it. It is an automatic life-sustaining process. Of course, we can interrupt the automatic mechanisms voluntarily. We can hold the breath, cough and laugh, examples of an important relationship between the voluntary and automatic mechanisms of a complex nervous system. If a failure occurs in the centers in the brainstem that control mechanisms of automatic breathing, this action ceases. Of course, when we are asleep, our voluntary control of breathing stops and we rely on the brainstem centers to control automatic breathing. A genetic defect in the brainstem centers causes a rare disease that has been called “Ondine’s Curse”. The patient can breathe voluntarily but automatic breathing ceases intermittently during the night, sometimes causing awakening with a startle. Life expectancy is short and the affected individual may die suddenly during the night. Many people reading this will become aware that I am also describing sleep apnea, which is really a less severe example of the same thing. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) has a similar history.

Thiamine Deficiency and Brainstem Function

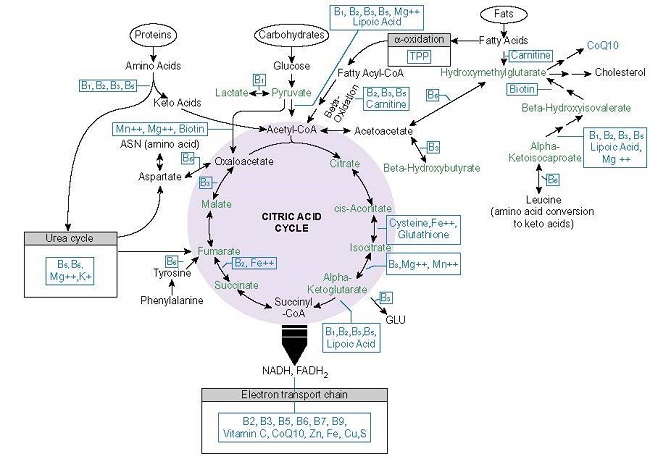

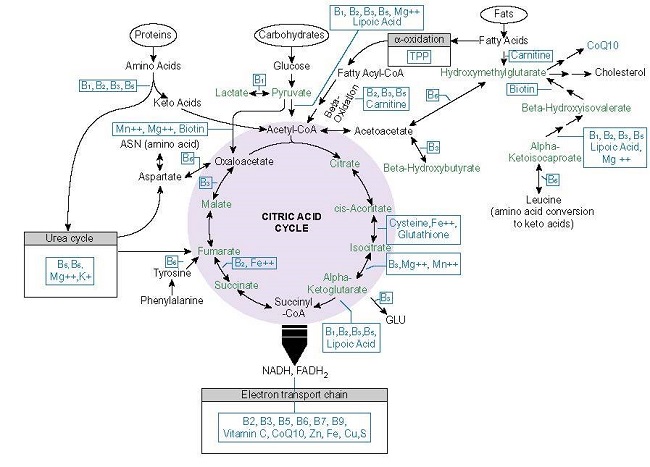

It has long been known that the lower part of the brain that includes the brainstem is highly susceptible to metabolic breakdown from thiamine deficiency. This metabolism is governed by an array of genes, some of which are activated in response to hypoxia (lack of oxygen). Because thiamine is absolutely essential to the consumption of oxygen (oxidation), lack of this vitamin is sometimes referred to as pseudo-hypoxia (false lack of oxygen). Therefore, a genetic defect in the automatic breathing mechanism might be affected by either hypoxia or pseudo-hypoxia, strongly implicating that a damaging effect might arise from either one, the other, or both together in combination.

I have successfully treated sleep apnea and threatened SIDS with pharmacological doses of thiamine and magnesium. A genetic error may not be a self-sufficient cause, requiring the addition of thiamine deficiency to precipitate the disaster. Now that we have the science of epigenetics (the ability of nutrients to react with the gene defect), it is, in my view, mandatory for a physician facing a clinical problem of this type to use pharmacological doses of thiamine and magnesium empirically. Even if it does not work, it can do no harm and might just save the day. To my knowledge, there are no pharmaceutical approaches available and it is unlikely that there ever will be unless the technique of gene replacement becomes a reality. Thiamine treatment even then should be the first line of approach because it is totally unstressful, nontoxic, cheap and I have seen some dramatic responses in my practice.

A Patient with Ondine’s Curse

Many years ago I had the care of a 12 year old girl who suffered from this disease. She was the child of a first cousin marriage and had lost two brothers from sudden death at night, so it was clearly genetically determined. I cannot remember the details, except that she was forced to use mechanical breathing assistance. As would be expected, she subsequently died. One day when we were studying her case, I was walking through the pediatric ward and noticed that she was sitting on the side of her bed. Her hands were raised in front of her with the fingers widespread; her eyes were staring and she was cyanotic (blue skin color). This was the position of great anxiety or panic, representing a fight-or-flight reflex. When she received oxygen administration, the cyanosis disappeared and she relaxed.

The Fight-or-flight Reflex

In many posts on this website, we have indicated that we have two types of nervous system. One enables us to move at will. The other one, known as the autonomic, is automatic and almost totally involuntary. This system, controlled by the lower part of the brain, including the brainstem, enables us to adapt to environmental change and governs the mechanisms for a number of important life-saving reflexes, the fight-or-flight being the best known. It can initiate mental and physical activity when a person is placed in a position of danger. It is not clear how the decision is made for flight or fight and this may depend on other factors in the personality of the individual. For example, a soldier may race up a hill, capture a machine-gun post and not know that he had a finger shot off in the process. It can imbue a feat of strength that enables a mother to lift the front end of a small car off her child who has been run over. Oxygen lack, as being experienced by my patient, was obviously exceedingly dangerous to her and fired the reflex, demonstrated by the characteristic positioning of panic. I treated this patient with thiamine, without effect, but had no regrets because I tried and there was no other treatment known.

Brain Chemistry and Genetics

The lower part of the human brain works rather like a computer or an information processor. It receives messages from the outside environment and signals the body organs through the autonomic nervous system. It is in constant communication with the rest of the brain. One of its important tasks is the maintenance of appropriate breathing. In the brainstem there are a series of cellular collections that since the status of oxygen concentration in the blood, thus enabling an adjustment in breathing appropriate to the oxygen concentration of the surrounding air. These centers are also sensitive to the efficiency of oxidation, the consumption of oxygen in the synthesis of energy. The first cousin marriage strongly suggests that my patient and her siblings succumbed to the effects of a genetic error. Aside from a genetic cause, one of the well-known weaknesses within this system is that this part of the brain is highly sensitive to a deficiency of thiamine, illustrated by the following case.

Mountain Sickness and Brainstem Thiamine Deficiency

A 75 year old woman came to my attention with a curious story. Every two weeks she would indulge in square dancing. On returning home she would succumb to a feverish episode that would last for several days. These episodes had, of course, been treated as infections, with little or no thought given to the association with square dancing. Laboratory studies revealed that she was deficient in thiamine, but in addition she had an abnormally high red blood cell count and hemoglobin. This is known as hemoconcentration and it would be expected to occur as an adaptive response to living at high altitude. In other words, an increase in hemoglobin and red cells would compensate for the low concentration of oxygen at high altitude. I concluded that the febrile episodes were an imitation of a well-known phenomenon known as mountain fever. Her brainstem was behaving as though the ambient oxygen concentration was equivalent to that of high altitude. However, the hemoconcentration compensation was insufficient because she had pseudo-hypoxia from thiamine deficiency.

Mountain fever occurs in people that have difficulty when they ascend to altitude and are said to be unfit for mountain climbing. Here was a woman that was developing this phenomenon at sea level. My explanation was as follows: her brain was marginally deficient in the vitamin necessary for oxidation and energy production for ordinary everyday purposes. The square dancing represented an additional consumption of energy for which some chemical adjustment had been made in her own system. Because this was insufficient the febrile episode imitated mountain sickness. These episodes disappeared after she was treated with pharmacological doses of thiamine.

Variation in Symptomology

It is obviously important to point out that this patient did not have Ondine’s Curse, even though oxidation was compromised in brainstem. Neither did my patient with Ondine’s Curse have mountain sickness. It represents an enormous difficulty in defining a clinical situation where two conditions are represented in different ways, although the underlying mechanism is similar if not identical. If this is the truth about disease, the symptoms that develop really represent an alarm system that has to be interpreted in terms of the underlying biochemical cause. Perhaps the focus on genetic causes may be too narrow and this seems to be true in cancer research. There is insufficient attention to epigenetic influence of nutrients on the action of genes and more attention should be paid to the nature of energy production in the mitochondria. Although both patients in this post had a widely different presentation, the underlying mechanism was similar if not identical.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image credit: Arthur Rackham, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

This article was published originally on June 25, 2018.

Rest in peace Derrick Lonsdale, May 2024.