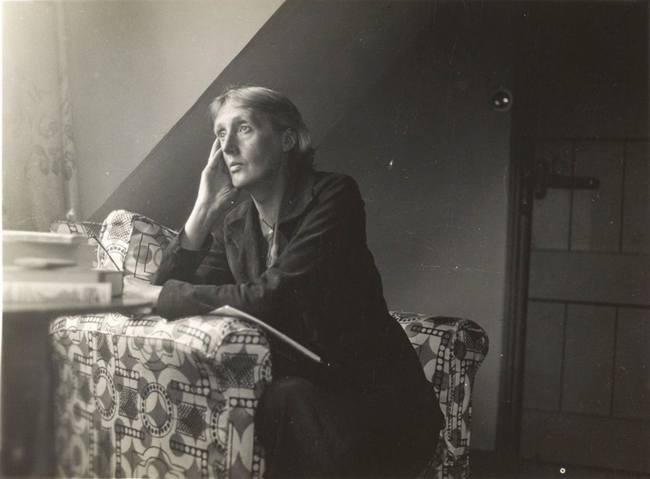

Virginia Woolf, an English writer who pioneered the use of stream of consciousness narration, was a tremendous diarist. Her diaries and her collection of autobiographical essays, ‘Moments of Being’1, reveal her longstanding struggle with health issues that today might be classified as Myalgic Encephalitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Reading her work for a creative writing class, I realized that her unrelenting fatigue, brain fog, and memory issues might have been due to unrecognized thiamine deficiency; an issue that I have struggled with, and published articles here and here and written two books about: The Missing Link in Dementia and Swimming in Circles.

‘My Brain Is Like a Scale’ – A Familiar Symptom of Thiamine Deficiency

Virginia’s diaries logged, in vivid detail, the symptoms she experienced – a condition which, like many today, had no clear diagnosis or treatment. She suffered with severe fatigue, ‘such an exaggerated tiredness’2(p.121), which fluctuated, ‘My brain is like a scale: one grain pulls it down. Yesterday it balanced: today it dips’2(p.260). The fatigue was noticeably worse after physical exertion, ‘But I am too tired this morning: too much strain and racing yesterday’2(p.263), but also deteriorated after socializing, ‘I’m too tired to go on with [reading]. Why? Talking too much I daresay. I thought, though, I wanted “society”’2 (p.230). Her symptoms recovered with rest – ‘A day off today’2(p.230).

In my memoir, ‘The Missing Link in Dementia’, I describe an illness characterized by extreme fatigue, insomnia, post-exertional malaise and significant memory problems. My condition progressively deteriorated, and I became extremely tired all the time. Severe insomnia left me restless most nights, and I would awake each day feeling unrefreshed and permanently exhausted. Any physical exertion, even walking, worsened the fatigue, my legs would feel heavy like dead weights, powerless and clumsy.

The most frightening symptom was short-term memory loss. I would spend hours reminiscing; spectacularly clear distant memories were more easily retrieved than any recent event. I experienced brain fog, reminding me of my pregnancy-induced woolly brain. I was forgetting things – outcomes of discussions or meetings at work, names, and then faces. I struggled to concentrate. I feared I was developing early dementia, and that my brain was becoming encased in amyloid plaques. In my memoir I described how I imagined these smothering my brain like a fleece in winter. Over time I steadily deteriorated with frightening moments of being unable to recognize my surroundings.

I wrote my memoir before reading the description of Virginia’s vivid memories of a happy childhood that were, ‘more real than the present moment.’1(p67). She tried to rationalize this experience – the strength of simple childhood memories compared with the weak later memories, describing ‘non-being’ as everyday activities that did not assimilate into our memory banks. She wrote, ‘I’m brain fagged’2(p.309), ‘I have already forgotten what we talked about at lunch; and at tea;’1(p70) but she knew that ‘although it was good day the goodness was embedded in a kind of nondescript cotton wool.’1(p70). Shortly before the end of her life she wrote: ‘I can’t concentrate’, ‘I can’t read’3. She had cognitive decline with short term memory loss.

The Emotional Component of Inadequate Thiamine

In contrast to my numbed senses, my emotions were far from muted, I was overly excitable or would burst into tears or become inappropriately angry at minimal provocation. I suffered with palpitations which were disconcerting, and at times, disturbing. Virginia wrote that she, ‘felt such rage’1(p125) and that her, ‘heart leapt: and stopped: and leapt again…and the pulse leapt into [her] head and beat and beat, more savagely, more quickly.’2(p.179)

I was scared, not knowing where to turn to for help. My quality of life was extremely poor. I had always been an optimist, but I could see no future living like this. I even contemplated suicide, because I did not wish to become a burden. I thought I was going to die anyway, and I was extremely sad that I wouldn’t see my children grow-up, but I thought that they would be better off without me. It seems terrible now – selfish even, but I was unable to control how I felt.

Virginia had suffered with an illness that had features of depression, she felt ‘such anguishes and despairs’2(p.94). She wrote that she was spoiling Leonard’s life. Tragically, she committed suicide in 1941 shortly after completing the manuscript of her last novel. She was 59. In her suicide note she wrote that: ‘Everything has gone from me’3(p.481).

Anorexia: A Cause and Consequence of Inadequate Thiamine

As a young adult Virginia had a stressful seven years with multiple deaths in the family1(p.117), sexual abuse during adolescence1(p.69), and probably had anorexia according to her great niece, Emma Woolf. Virginia was almost 6 foot and weighed 7st 6lb (104lbs) when she was institutionalized for rest and feeding, her body mass index (BMI) was 14.5, a marker that she was significantly underweight.

I found out in my forties that I had a congenitally malrotated gut, presenting unusually as an adult. I had developed marked slowing of my guts, so that it was becoming impossible to eat. The slowing of my guts meant that I no longer felt hungry. I had to remember to eat, to force myself to eat. I lost weight, dropping from size 12 to 6. I lost muscle mass; where previously I had muscles there were now gutters. The muscles were constantly twitching – fasciculation’s, tics, tremblings or flutterings.

Neurasthenia: The ME/CFS of the Time

It is likely that Virginia was influenced by Jane Austen. Virginia’s first novel has many links to Austen’s novels, including the names of characters. Famous quotes from Austen’s Pride and Prejudice hint at Mrs. Bennet’s underlying condition: ‘Mr. Bennet…You have no compassion on my poor nerves.’4(p.7), ‘…I am frightened out of my wits; and have such tremblings, such flutterings, all over me, such spasms in my side, and pains in my head, and such beatings at heart, that I can get no rest by night nor day’4 (pp.273-4).

Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen’s Mrs. Bennet were both thought to have suffered with neurasthenia, literally weak nerves, a term originally used in the nineteenth century United States, when it was associated with busy society women and overworked businessmen. The first description of neurasthenia was published by American neurologist Beard in 1869. Virginia wrote that she was ‘extremely social…for ever lunching and dining out…or going to concerts…and coming home to find the drawing room full…of people.’1(p.163) She was obliged to participate because the ‘pressure of society was now very strong.’ 1(p.128) She repeatedly spoke of a ‘world of dances and dinners’1(pp.170, 172).

Low Thiamine Causes Low Energy Levels

One of the problems in ME/CFS/neurasthenia is that there are no tests. A clue is that the predominant symptom is fatigue. After excluding other causes of fatigue, a prime suspect must be faulty energy production. Another problem in ME/CFS/neurasthenia is that there is a lack of understanding about the basic energy producing processes or the fact that thiamine, or vitamin B1, is crucial.

ATP (adenosine with three phosphates) is the main energy currency. Energy is released each time a phosphate group is removed from adenosine, becoming ADP (adenosine with two phosphates). This is the human equivalent of a rechargeable battery.

Respiration is the breakdown of food-fuel to release energy. The predominant fuel, glucose, is broken down to produce pyruvate via glycolysis – literally glucose breakdown. This pathway doesn’t require thiamine (or oxygen). It produces two ATP. This is just small change in comparison with the energy produced in the battery factory – mitochondria.

Entry into the battery factory is through the gatekeeper enzyme – pyruvate dehydrogenase. This enzyme breaks down pyruvate, and importantly, requires thiamine as a co-factor – it malfunctions without thiamine.

Once inside the factory there are two production lines: one continuously uses recycled components (tricyclic acid cycle) and the other is a chain of reactions (electron transfer chain). These processes make significantly more ATP, producing more charge, more efficiently – like ultra-rapid charging for EVs. Obviously, this is a simplified version to hammer home the message that thiamine matters. A more accurate, detailed and scientific (less creative) description can be found here.

A shortage of thiamine (or oxygen) results in the excess pyruvate being converted to lactic acid. A familiar sensation to anyone who has sprinted 100m, when the demand for energy is higher than production, is the build-up lactic acidosis in the muscles, causing cramping, burning or weakness. This diversion of metabolism to an anaerobic (without oxygen or thiamine) pathway is inefficient, because another chemical reaction, requiring yet more energy, is required for the muscles to remove the lactic acid and recover. This results in an energy debt as it costs more energy to return the lactic acid to the usable pyruvate – akin to buying back the family silver from the pawn shop.

During exertion thiamine is required to ensure the higher power charge is readily available. Excess lactic acid results when energy requirements outstrip production, whether from a lack of oxygen or thiamine. In patients with ME/CFS, lactic acid accumulates more readily during exercise and before oxygen supplies are exhausted, and an elevated lactic acid level is found in the fluid surrounding the brain. Malfunctioning pyruvate dehydrogenase has been identified as key in ME/CFS. These patients feel like they are doing a 100m sprint whenever they try to walk. The (now debunked) treatment of patients with ME/CFS with exercise therapy, shows that their condition was misunderstood.

For those with a more sedentary existence, falling asleep with an arm above your head gives the same sensation. When the blood starts to circulate the arm temporarily feels like a dead weight. The arm is incredibly weak and lacks coordination. This is because the nerves no longer respond to the instructions from the brain.

Weak Nerves? Think Thiamine.

Nerves are highly susceptible to thiamine deficiency. The poorly insulated nerves – the autonomic nerves – are particularly vulnerable to thiamine deficiency. These autonomic nerves control the fight and flight response and regulate gut movement, sweating and heart rate – the ‘housekeeping’ functions which are outside voluntary control. After prolonged thiamine deficiency, eventually all nerves are affected, including the larger, better-insulated sensory and motor nerves. Arguably, the term neurasthenia is more appropriate than ME, it indicates the underlying problem – reduced nerve function.

According to the hypothesis that I describe in my memoir, excess thiamine-destroying bacteria, in the part of the gut responsible for absorbing nutrients, reduce thiamine availability. Vitamin D deficiency is common in bacterial overgrowth; it makes sense that it is a surrogate marker for thiamine deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency often occurs in patients with ME/CFS.

Rest, Recover, and Recharge

Back then, the best treatment for neurasthenia was the ‘rest cure’. Beard, a sufferer himself, astutely remarked that it was due to the body being drained of nervous energy due to an overtaxed supply of energy. Virginia was treated with rest and recognised that her nerves required respect: ‘Only nerve vigour wanted’2(p230). She was also treated with a high protein diet. Similar approaches have been popularised today. Diets such as paleo, South Beach and Mediterranean support a higher protein consumption. I ate a low carbohydrate diet for years and still avoid sugar now. I also took thiamine supplements, had corrective gut surgery and antibiotics. Popular techniques for resting the mind and body include meditation, yoga, relaxation and mindfulness. Resting helped me. It wasn’t easy, because I felt agitated and compelled to move. I spent hours doing jigsaws, aware that I was recharging my batteries – a term I’ve used but not reflected on. Strangely, this is the underlying problem: low charge, faulty charging, poor battery capacity. We have a far better understanding of modern technology that has been around for a few decades than the human system in existence for millennia which is reliant on thiamine.

Thiamine Deficiency, Modern Lifestyle, and Sugar Cravings

Humans have some design glitches predating our modern lifestyles. The first anomaly is that ATP is not stored, and the ATP generated is used 1000 times over each day – the body must constantly produce and recycle ATP. The second design fault is that thiamine, despite being essential, is not stored and is only poorly absorbed through the gut. Low thiamine levels are prevalent in society, leading to faulty recharging of our internal batteries.

Beard, who wrote about his neurasthenia in 1869, thought it was due to American modernization. He was right; we have made poor lifestyle choices. In the United States, sugar became readily available after 1864, following the civil war, with the construction of the biggest sugar refinery in the world on Long Island and a reduction in taxes. In the UK, sugar consumption escalated a century earlier, Britain was described as the ‘sweetshop of Europe’, thought to be in part due to our tea-drinking habit. By the time Jane Austen was writing, sugar was Britain’s most valuable import. Originally a condition affecting the upper classes, neurasthenia spread to the lower classes, as sugar became more affordable, although this may reflect access to medical care.

I had been craving sugar for years to gain short bursts of energy as I flagged, adding sugar to tea, one teaspoon became two, then three. Like topping up a meter constantly with small change, the sweet tea momentarily cleared the brain fog, allowing me to see another patient or simply make it to the end of the day. I experienced the same sensation in my colleague’s office after a dose of intravenous thiamine – the cotton wool vaporized.

The brain only uses glucose for energy production, whereas muscles can use protein as a fuel. I now understand that by drinking sugar-charged tea I had been supplying my glucose-dependent brain with glucose for the glycolysis pathway but because I was deficient in thiamine, the products of glycolysis could not enter the TCA cycle and progress to the electron transport chain where most of the ATP is made. The sugar craving was a sign that my brain was starving – desperate for energy – for titbits of ATP.

Factors Affecting Women

ME predominantly affects women. In many cases there is a deterioration during the peri-menarche or perimenopause, times of marked growth and/or hormonal changes. Progesterone slows gut motility. Estrogen improves nerve connections in the hippocampus – the part of the brain responsible for working or short-term memory, it also increases glucose uptake into the brain.

Being perimenopausal, my falling estrogen levels meant that the brain uptake of glucose was less efficient. Glucose offered short-term relief but exacerbated the bacterial overgrowth and malabsorption. It was clear that I had been breaking down muscle and using it as a protein source to produce energy outside my brain, contributing to the muscle wasting I experienced.

Thiamine is depleted during pregnancy, breast feeding, growth, infections and exercise. Having had four children, all breast fed, I had started exercising to get fit, and lost weight, initially intentionally. Other familial factors, immune deficiency causing recurrent infections or defective thiamine uptake genes, might have contributed. I had multiple factors, any one of which would deplete thiamine.

Was Virginia Woolf Deficient in Thiamine?

We will never know. What we do know though is that thiamine deficiency leads to poorly functioning housekeeping nerves and slow guts, predisposing to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. This causes reduced appetite, trouble eating, reducing thiamine intake further. It is a physical problem caused by vitamin deficiency, poor nerve function initially, and eventually, nerve damage. Thiamine deficiency is treatable. It is not a psychiatric illness – the mental symptoms I experienced were caused by thiamine deficiency. Virginia Woolf was probably thiamine deficient too, having suffered with anorexia nervosa. She had a diagnosis of neurasthenia, now known as ME/CFS. Millions of people suffer with ME/CFS. Perhaps it is time we look into thiamine.

References

- Woolf V. Moments of being unpublished autobiographical writings. Schulkind J (ed). New York and London: Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich; 1976.

- Woolf V. A writer’s diary: being extracts from the diary of Virginia Woolf. Woolf L (ed). New York: Harcourt inc.; 1953.

- Woolf V. The Letters of Virginia Woolf. Vol. 6, 1936-1941. Nicolson N, Trautmann J (ed). London: The Hogarth Press; 1980.

- Austen J. Pride and prejudice. Vivien Jones (ed). London: Penguin Classics; 2003.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image credit: Harvard University library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.