In a previous article, I wrote about how, as a DES daughter, I felt I had a distinct advantage of gaining my understanding of cervical cancer and cervical screening programs before the human papillomavirus (HPV) was even detected; and before HPV tests and HPV vaccines were developed and marketed. I think I would have struggled to understand the issues involved in screening for cervical cancer if trying to do so just in the last decade. With all the media hype, controversy, and general confusion that abounds in this area of women’s health, gynecological care has become increasingly difficult to navigate.

In Australia where I live, on 1 December 2017 radical and sweeping changes are about to be made to the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) that will impact women’s health significantly. I should note, although I focus on the changes made being made to the NCSP in Australia, other countries have considered or have introduced similar programs. These programs affect how and when cervical cancer screenings take place and, more importantly, whether and which types of cancer will be detected.

Cervical Cancer Screening in Australia

Introduced in 1991, the current NCSP offers routine biennial Pap smear screening for all women aged 18-69 years. Commencement age is 18 years, or two years after beginning sexual activity (or ‘sexual debut’, as it is quaintly termed), whichever is the later. The program has had great success. As a result of its introduction, both the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer has halved to one of the lowest in the world.

“Cervical cancer incidence for women of all ages remains at an historical low of 7 new cases per 100,000 women, and deaths are also low, historically and by international standards, at 2 deaths per 100,000 women.” Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Now this is all under threat and the NCSP as we know it is about to be decimated. Rather than focus on cervical cancer detection, and thus, prevention, with biennial Pap smears, the new program will rely primarily on HPV vaccination and triage HPV testing. The Renewed NCSP will offer a “cervical screening test” to women only at 5-yearly intervals, and only beginning at age 25 years.

Moreover, this “cervical screening test” will not be the Pap smear. Women will only have a Pap smear if they test positive to HPV. Not only is HPV testing being introduced for the first time as a public health screening strategy; it is being fast-tracked to become the PRIMARY screening tool. This means a Pap smear will only be subsidized by the Government under the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) if you first test positive to HPV.

This is a huge and, I would suggest, risky change to the cervical cancer screening program. The Renewed NSCP is based on predictive statistical and economic modelling around the HPV vaccine and triage HPV testing.

There is little regard for the empirical evidence and lessons learned from the 70+ years since the Pap smear test was developed; the 50+ years of organized cervical screening in Australia; and the 26 years of empirical evidence and reporting from the world-acclaimed NCSP. All this accumulated evidence and wisdom is seemingly being ignored, and this worries me. As a DES daughter I believe it is crucial that we remember and learn from past experiences.

Understanding the Reproductive Tract and Cancer

The aim of population cervical cancer screening programs directed specifically at asymptomatic women is to reduce the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. In order to understand why relying on the HPV vaccine and triage HPV testing to prevent incipient cervical cancer is problematic, it is important to understand the types of cervical cancer. Bear with me, this information is a bit technical and complicated, but it is critically important for women to understand the differences to enable educated choices about reproductive health.

Two Types of Cervical Cancer

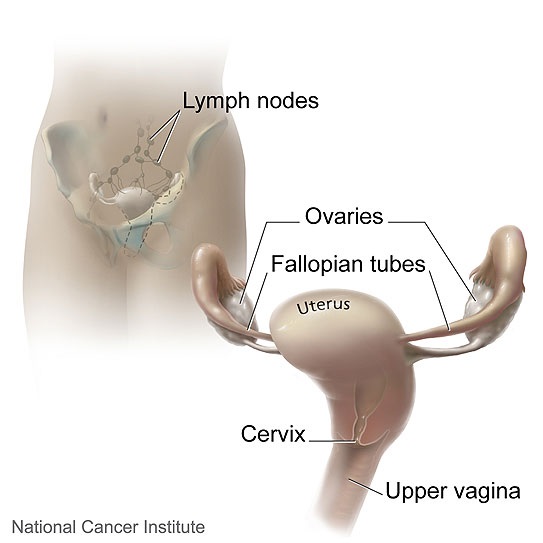

Cervical cancer affects the cells of the uterine cervix, which is the lower part (or ‘neck’) of the uterus where it joins the inner end of the vagina. It is where the Mullerian-derived glandular tissue from the upper genital tract meets the squamous tissue of the lower or outer genital tract.

Anatomy of the Cervix and Nearby Organs

Source: National Cancer Institute<NCI Visuals Online>Illustrated by Don Bliss

Cancers of the upper genital tract (e.g. of the ovaries, Fallopian tubes and endometrium) are glandular cell cancers. Cancer of the cervix can be either squamous or glandular.

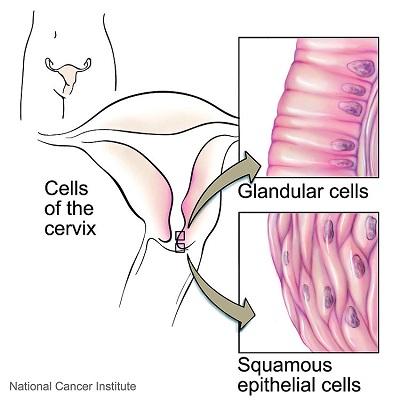

The Cells of the Cervix

Source: National Cancer Institute<NCI Visuals Online>Illustrated by Don Bliss

There are two types of cervical cells – squamous and glandular. The Pap smear takes sample cells from the transformation zone of the cervix where the squamous cells and glandular cells meet. This is where most cervical abnormalities and cancer are detected as the cells are undergoing constant change. The sample cells are then examined under a microscope for any abnormal (dysplastic) change. Any abnormalities (both squamous and glandular) are then classified and graded by the cytologist.

Squamous Cell Abnormalities and Cancer

Any abnormal changes to cervical squamous cells typically have a long lead time before cancer, with several preliminary stages before invasive cancer. It is not an inevitable linear progression, as the vast majority of low-grade squamous abnormalities resolve without treatment. Even many high grade abnormalities may regress; if not, they can be treated by a range of procedures.

The terminology has changed over the years, but all the following terms refer to squamous-cell abnormalities: mild, moderate and severe dysplasia; squamous carcinoma in situ (SCIS); HPV effect, HPV wart effect; cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN); CIN1, CIN2, CIN3; squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL); LSIL and HSIL.

It is critically important to realize that HPV infection relates ONLY to squamous cell abnormalities.

“The papilloma viruses are attracted to and are able to live only in certain cells called squamous epithelial cells. These cells are found on the surface of the skin and on moist surfaces (called mucosal surfaces).”

Source: American Cancer Society

Glandular Cell Abnormalities and Cancer

Like the glandular cancers of the upper genital tract, cervical glandular cancer is more aggressive and has a shorter lead time. There are two precursors to (invasive) adenocarcinoma: atypical glandular cells and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). In practice there is no ‘low grade’ glandular-cell abnormality, as any atypical change is referred for immediate colposcopic investigation. Cervical adenocarcinoma is a relatively new phenomenon, with AIS being first described in 1953.

The Success of the Pap Smear and Cervical Screening Programs

The Pap Smear

The Pap smear is named after Dr. George Papanicolaou who developed the test in 1943 . A sample of cells is collected from the transformation zone of the cervix. With the conventional Pap smear, the cells are smeared onto a glass slide, stained and examined under a microscope for any abnormalities. Liquid Based Cytology (LBC) is a newer technology that involves a different method of preparing cervical samples for examination. The cells are placed in a vial containing preservative liquid. The sample is then sent to the laboratory for processing to remove obscuring material before being placed on a slide.

Any cell abnormalities (both squamous and glandular) detected on cytology are then classified and graded, as discussed above. Hence, the Pap smear detects the early precursors of both types of cervical cancer.

The Pap smear became widely accepted as a very effective screening test for cervical cancer: In countries that had programs, morbidity and mortality from invasive squamous cell cancer was considerably reduced.

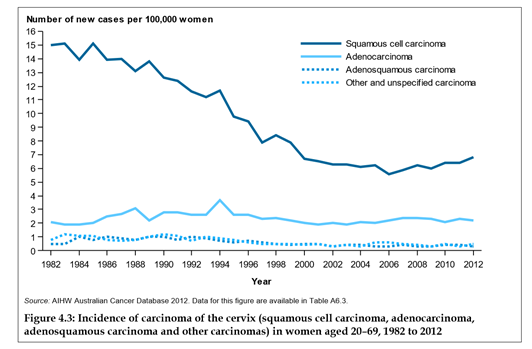

It can be seen in the following diagram that in Australia the incidence of squamous-cell cancer was more than halved between the years 1982-2002.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Of the cervical cancers diagnosed in 2012, 69.3% were squamous cell cancer. Figure 4.3 shows that for the last 15 years, the relative incidence between squamous and glandular cancer has remained more or less constant at around 70% and 30%, respectively.

The empirical data from the NCSP shows consistently that the biggest risk factor for cervical cancer is not having regular biennial Pap smears. Of Victorian women diagnosed with cervical cancer, 40% had never been screened, and a further 35% were “lapsed screeners” (that is, they hadn’t had a Pap test in the 2.5 years prior to their cancer diagnosis).

Whereas routine Pap screening programs dramatically reduced invasive squamous cancer in Western nations; without proper infrastructure and resources, the rates of cervical cancer in developing nations remain high. That the global burden of cervical cancer is greatest in developing countries is shown in Figure 1, Cervical Cancer: A Preventable Death.

HPV and HPV Testing

HPVs are a group of more than 150 related viruses. Each HPV virus in the group is given a number, which is called an HPV type or strain. The papillomavirus viruses are attracted to and are able to live only in certain cells called squamous epithelial cells. These cells are found on the surface of the skin, and on moist surfaces (called mucosal surfaces). Of the more than 150 known strains, about 75% HPV types are called cutaneous because they cause warts on the skin. The other 25% of the HPV types are mucosal types of HPV, and genital HPV types are in this group.

Source: American Cancer Society

Genital HPV is a very common sexually transmitted infection (STI). It is spread mainly through intimate direct skin-to-skin contact. It’s not spread in blood or other bodily fluids. Genital HPVs are classified as “low risk”: HPV types that tend to cause warts not cancer; or “high risk”: oncogenic HPV types that have the potential to cause cancer.

Like any virus, genital HPV continually evolves and mutates. In Australia of the 40 known genital HPV strains, 15 are considered oncogenic, with HPV types 16, 18 and 45 being the most prevalent.

Infection with one or more of the 40 HPV types is very common. HPV is such a prevalent STI that it could be considered a normal part of being sexually active. Most people will have HPV at some time in their lives and never know it. It is asymptomatic. You may only become aware of HPV is you have an abnormal Pap smear result or if genital warts appear.

Although HPV infection is very common, in most people it clears up naturally in about 8-14 months. In a small number of women, the HPV stays in the cells of the cervix. When the infection is persistent, not cleared readily, there is an increased risk of developing squamous CIN abnormalities.

The HPV Test

In contrast to the Pap smear, the HPV test is not a test for cancer. Cells are collected from the cervix as with a Pap smear but then in the laboratory undergo HPV genotyping to see if one or more oncogenic HPV types are present.

The proposed primary triage HPV test in the Renewed NCSP involves partial HPV genotyping. According to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC), the authority overseeing the Renewed NCSP, the HPV test must have HPV genotyping capacity to identify HPV 16, 18, and possibly 45.

HPV and Primary Cause Theory

In countries that don’t have Pap smear screening programs, the burden of invasive squamous cancer is great. The precursor CIN abnormalities cannot be detected and hence can progress to invasive cancer. HPV testing provided the tool to look at HPV genotype distribution in invasive and pre-invasive cancer in developing countries. Significant geographic differences in HPV type prevalence were found in different regions worldwide.

During the 1990s hundreds of studies, both large and very small, were undertaken in countries that didn’t have Pap smear screening programs. Meta-analysis of these studies led to the premise that HPV is the primary cause of squamous cancer: Infection with a persistent oncogenic HPV type is the necessary first step before any precursor CINs can develop. This premise that HPV is the primary cause of squamous cell cancer is shown diagrammatically in Figure 1 Natural history of HPV infection and cervical cancer on page 13 of the Medical Services Advisory Committee (2014) MSAC Outcomes – Application No. 1276 report.

In developing countries without Pap smear screening programs, a primary triage HPV testing strategy makes sense.

“In populations where cytology programmes are either not in place or are not efficient, HPV testing should now be considered and evaluated as an alternative test for primary screening.” Source: Bosch et al (2002)

Women who test positive to oncogenic HPV types can then be prioritised to access the limited health care resources available.

This strategy does not make sense, however, in countries with routine Pap smear and gynecological care; and where 30% of the cervical cancers diagnosed are glandular-cell cancers.

If HPV Tests Do Not Detect Cancer, Why Are We Replacing the Pap Smear?

This is a very good question.

An even better question is: Why would you have a Pap smear and not find out the result?

As of 1 December, Australian women will be offered a “cervical screening test”. They will have a LBC Pap smear, where the cervical cells are placed in a vial containing preservative liquid. Instead of being sent to a cytology lab to be screened for cell abnormalities, the vial will be hijacked to a lab for partial HPV genotyping. If it tests positive to HPV 16, 18, or (possibly) 45, the same specimen of cells will then be reanalysed using reflex cytology to see if any squamous or glandular cell abnormalities are present.

How bizarre is that? How very Kafkaesque.

Let’s take a deep breath and heed some wisdom from the recent past. According to the NCSP webpage (2009):

Should I have a special test for HPV?

There is an HPV test available which can identify strains of HPV. This is not a test for cancer…

Because most HPV infections usually resolve naturally, and there is not cure, there is little reason to have an HPV test…

While a Pap smear cannot identify which type of HPV is present, regular Pap smear will make sure any changes that occur are identified early and managed effectively.

The Bottom Line on Pap Smears Versus HPV Testing

The Pap smear is a screening tool that detects CIN abnormalities and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), the precursor to adenocarcinoma.

While HPV is the primary cause of squamous cancer; evidence from the NCSP consistently and conclusively shows that the biggest risk factor for cervical cancer is not having regular biennial Pap smears.

Bottom line, the Pap smear detects abnormal cervical cells, both squamous and glandular, and is a long established, very successful screening test for cervical cancer. The HPV test screens for a STI. As a woman, I would argue for a regular Pap smear.

We Need Your Help

More people than ever are reading Hormones Matter, a testament to the need for independent voices in health and medicine. We are not funded and accept limited advertising. Unlike many health sites, we don’t force you to purchase a subscription. We believe health information should be open to all. If you read Hormones Matter, like it, please help support it. Contribute now.

Yes, I would like to support Hormones Matter.

Image by Hilary Clark from Pixabay.

This article was originally published on June 27, 2017.

There’s actually no way of knowing whether pap smears have saved lives from cervical cancer because the deaths from cervical cancer were actually declining at a steady rate before the test was introduced due to factors like improved nutrition and hygiene etc.

It is possible that the reason for it’s so called ‘success’ is that self-selecting women who are health conscious tend to opt for the test, who were less likely to get cervical cancer anyway. There’s no accurate way of knowing whether smear tests really have saved lives, and the whole screening process causes a huge amount of harm to women, often ignored behind those statistics of lives saved. This is an article I wrote for Hormones Matter about my experience https://www.hormonesmatter.com/sexual-trauma-leep/

The Parent Paradox by Dr. Margaret McCartney is a really good book to read for looking at the way cervical screening success rates are utterly manipulated to persuade women to have these tests.

Women should be aware of risks and harm whether they opt for HPV test, pap smear or nothing at all. In my experience I have had far greater harm, than if I had avoided testing completely.

You appear to be confusing two separate issues – Pap smear screening vs. the Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure (LEEP) procedure – and are essentially “shooting the messenger”. Both your and Asha’s experiences concern inappropriate or overzealous use of LEEP which, in turn, raise questions around the adequacy of education of service providers, problems with communication between patient and service provider; and the issue of informed consent.

Cervical cancer was not steadily declining before the Pap smear was devised. The Pap smear was developed in 1943, around the same time that exogenous oestrogens were synthesised and marketed. As explained by Barbara Seaman in The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth (2003), when these exogenous oestrogens were marketed to treat menopausal symptoms during the 1940s, and later as the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) from 1960 onwards, the incidence of gynecological cancers (breast, endometrial and cervical) increased dramatically.

In 2007 the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified OCPs as a Group 1 carcinogen in humans: “There is sufficient evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of combined oral estrogen–progestogen contraceptives. This evaluation was made on the basis of increased risks for cancer of the breast among current and recent users; and for cancer of the cervix…”

There is extensive documentation of the success of the cervical screening programs. For example, cervical cancer screening was first trialed in British Columbia in 1949. Program evaluations between 1955 and 1985 showed that morbidity and mortality from invasive squamous cell cancer of the cervix had been considerably reduced, and was directly attributable to the screening program. [Anderson et al (1988) Organisation and results for the cervical cytology screening programme in British Columbia, 1955–85]

In the above article, Figure 4.3 ‘The incidence of carcinoma of the cervix’, shows the incidence of squamous carcinoma was more than halved between the years 1982 and 2002. Factors such as improved nutrition and hygiene would not be playing a role in that time frame.

In a previous article, I explained how DES daughters have become, through experience, “experts” when it comes to the difference between squamous and glandular cell abnormalities and cancer. https://www.hormonesmatter.com/save-pap-smear-des-daughters-perspective-cervical-cancer-hpv-vaccine/

When I was young (and I swore I’d never use that phrase!) and having Pap smears during the 1970s, it was usual when it came to squamous cell abnormalities (or dysplasia as it was called then) to “wait and see”; “have another Pap smear in 3-6 months”; “get a second opinion if you’re not sure”. It was a time of questioning, and seeking out information to enable informed decisions. There was great work being done by the Boston Women’s Health Collective and other women’s health networks. Books such as Our Bodies Ourselves were exploring issues such as the effect of hysterectomy on sexual function, and many of the issues you and Asha are raising.

I find it frustrating that this traditional knowledge base has somehow been lost. Why do women have to reinvent the wheel?

Of course, as I tried to stress in my articles, this conservative “wait and see” approach ONLY applies to squamous cell abnormalities. There is no “wait and see” with glandular cell abnormalities. If any atypical glandular cell abnormalities are detected, there should be immediate follow-up with colposcopic investigation.

As to whether smear tests really have saved lives, here is my daughter’s story:

https://www.hormonesmatter.com/pap-smears-saved-life-cervical-cancer-after-gardasil/

And two very similar stories:

http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/cervical-cancer-i-didnt-think-it-would-happen-to-me/news-story/3ac9e6fbf97ddac8ffe2bd710533db87